Enjoy our latest podcast episode, #62.

It is a 60-minute listen or 39-minute read (scroll down for a full transcript).

This conversation reminds us that the current systems that keep us from achieving equity and inclusion weren’t just an accident of evolution. They were designed—intentionally designed. These past designs and their artifacts also persist in our everyday lives, even when we have stopped many of the harmful practices. Today's guest, Braden Cooks of Designing the We, will share how we can undesign our current systems of inequity and separation and imagine new ways for our communities to design and build a more equitable future.

AUDIO PLAYER

You can access it wherever you listen to podcasts via our pod.link.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

Learn more about Designing the We and Undesign the Redline.

Learn more about participatory budgeting and how to implement it in your community at the Participatory Budgeting Project.

Read more about community investing in this article from Barron's site Penta.

Also, you can download the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's report, Impact in Place: Emerging Sources of Capital and Strategies to Direct it at Scale.

Braden recommended Mindy Thompson Fullilove's writing to me. I'm currently reading her book Main Street: How a City's Heart Connects Us All. He also recommended her book Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do about It. If you'd like to read more, these would both be great accompaniments to this episode.

BRADEN'S BIO

Braden Crooks has over a decade of experience in leadership roles in the space of design and community development. He is a founding partner at Designing the We, a for-purpose design studio supporting community, social and economic development. dtW are the creators of the nationally renown exhibit, Undesign the Redline. The dtW team designs plans, programs, policies and enterprises together with local communities, governments, institutions and organizations who are dealing with deep crises, from the history of Redlining to the future of work.

Braden is Chair of the board of The New York State Sustainable Business Council, which represents over 3,000 businesses championing an equitable and sustainable economy in New York State. Braden graduated from the innovative program MS Design and Urban Ecologies at Parsons, has taught ecological thinking in urban issues and produced a live audience webseiresabout art and activism in New York City. He lives and gardens in Brooklyn, NY.

FULL TRANSCRIPT

-Introduction

Ame Sanders 00:11

This is the State of Inclusion podcast, where we explore topics at the intersection of equity, inclusion, and community. In each episode, we meet people who are changing their communities for the better, and we discover actions that each of us can take to improve our own communities.

I'm Ame Sanders. Welcome.

In my past corporate career, I last worked in marketing alongside teams that focused on product design. So, when I heard about Designing the We, I couldn't wait to talk to its co-founder, Braden Cooks. This conversation reminds us that the current systems that keep us from achieving Equity and Inclusion aren't just an accident of evolution. They were designed. They were intentionally designed. And as you'll hear in this episode, these designs and their artifacts persist in our everyday lives, even when we have stopped many of the harmful practices around them.

In our discussion with Braden, he'll share how we can undesign our current systems of inequity and separation and imagine new ways that our communities can design and build a more equitable future. Before we start, a small aside. You know, our guests freely share their stories with us. So, we make the podcast or newsletter and related content free as well. However, if you'd like to support us grow in our work and help to offset some of our production costs, you can find a link to our Support Us page in the show notes. We're happy that you found us. We're grateful that you listen, and we would be thankful for your support. So today, we're happy to welcome Braden Cooks. Braden is a co-founder of Designing the We. Designing the We is a for-benefit social design studio. Welcome, Braden.

Braden Cooks 02:12

Happy to be here. Thanks for having me.

-About Designing the Wed

Ame Sanders 02:15

I've been intrigued by your work, I have to say. Maybe I should start by just asking you to tell us a bit about Designing the We and maybe what you mean by a "for-benefits social design studio."

Braden Cooks 02:28

Yeah, absolutely. Designing the We was started by myself and April De Simone, actually out of grad school. We really felt that the type of work that we wanted to do, it was really community-driven. It was innovative and sort of pushing the needle. We weren't seeing enough of and we wanted to kind of champion that.

When we say for-benefit design studio, for one, we are mission-driven. We're not necessarily a nonprofit, but we are mission-driven. That is at the core of what we're doing. You know, social design studio, we just think about human beings and relationships. It's called Designing the We, and it's really how do those types of relationships form and how do they become more equitable? How do we really look at the way those relationships are structured, both on really a human scale and on a larger scale, more systems-wide, and really center people in that?

-About Undesign the Redline

Ame Sanders 03:27

So maybe the way to better understand your work is to talk about one of your maybe your best known signature project Undesign the Redline. Could you tell us a little bit about that project--what it is, how it works, and how it's been used in communities across the country?

Braden Cooks 03:45

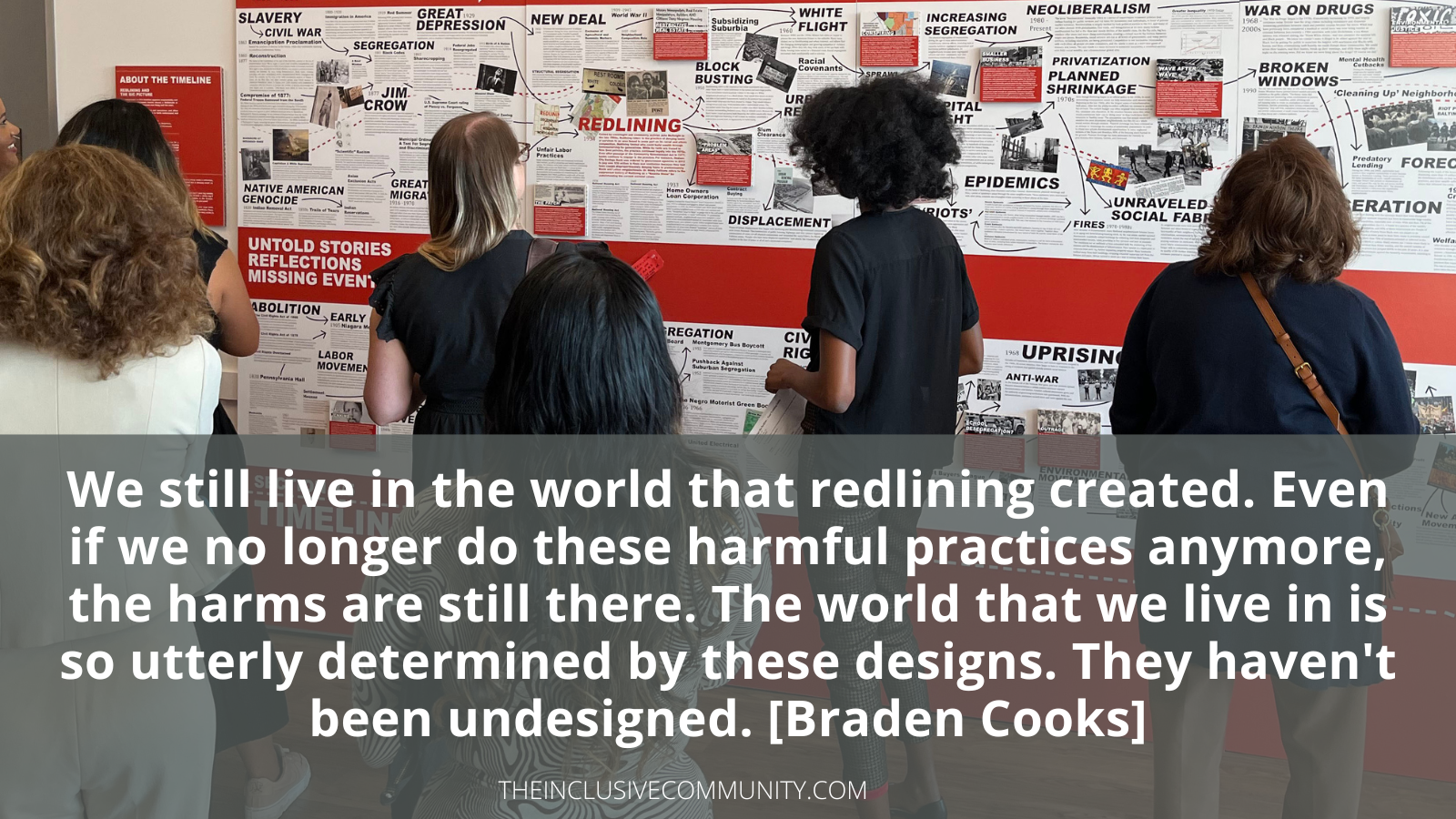

Yeah, that project really launched Designing the We and has been in many ways been the centerpiece and the bulk of our work. It's really a platform, and it unpacks and demystifies the history of redlining in particular, but a lot of urban policies, a lot of design decisions in many ways and practices that got us to where we are today. We found that when people were sitting around the table, asking "What should we do next?" They weren't coming with a shared story of how we got here. That's really what it tries to do, is tell the story of how did we get here? Why do our communities look the way we do? Why does one neighborhood look one way and another another? It ripples out into every aspect of our life—place.

Your zip code is your number one determinant of life expectancy, education, access to opportunity, you name it. All these things that determine in many ways, what are the quality of our own lives all take place in cities, towns, places, neighborhoods that were designed. Policies like redlining, which really systematically disinvested in neighborhoods and cities based on race, was so transformative--in a bad way--policy for what happened later on. I mean, decades and decades. The legacy of this goes on. You look at how urban renewal and the bulldozing of many neighborhoods falls along that same path. You can look at where placement of environmentally degradating pollution– it's concentrated in some neighborhoods and not others.

These cumulatively have huge impacts on just how uneven our world is, where some people get a real head start, and other people are really pulled back. That's on the basis of race, class, and all these things. So, part of looking at redlining was to say redlining is something that formally we've said is illegal, right? We can't do redlining anymore. You can't say we're gonna deny loans to a particular neighborhood or particular race of people. But in some ways, that still goes on, believe it or not. There are lawsuits for redlining every year across the country in different places where banks are loaning and doing things under the table. But even if you say, yeah we've stopped these harmful practices, we still haven't gone back and undone the legacy that these created. The really intergenerational, profound gulf. The racial wealth gap. Just the way neighborhoods look, the different access to opportunity. We still live in the world that redlining created, even if we've said, "Yeah, we no longer do these harmful practices anymore." The harms are still there.

That's sort of where we're stuck as a society, is in this space, where, on the one hand, you have people saying, "Hey, this is over. We don't need to worry about it anymore." And then on the other hand, the whole world that we live in is so utterly determined by these designs, so they haven't been undesigned. That's really where the title of the exhibit comes in as a way to talk about this history because it's just a history we haven't told. I mean, I wasn't taught about it in school, certainly up until much later years in grad school. As a society, it's just something that we don't really understand and we don't really fully grasp. Because of that, people have all kinds of mythologies. They say, "Well, you know, people just don't work hard enough. They're lazy. They make mistakes." Then that's why we see the poverty we do. "My family pulled ourselves up by the bootstraps." It's not to negate, you know, sure people work really hard. But lots of people working really hard, and they still fall behind. That's because of these systems.

So, our hope in bringing that exhibit--we brought it to, I don't know, more than two dozen cities--is really to create a public conversation around this history and invite everyone at the table to say, "Well, how can I participate in charting a different direction?" It's not about blaming or shaming people. It's really about inviting people to the table to say, yeah, we can change this. If this was done intentionally. If this was designed intentionally, it can be undone. So, let's do it.

Ame Sanders 08:16

So, maybe you can just let the listeners in on what the platform and exhibit are like. What are the elements that you have that make up the Undesign the Redline? How do communities take the pieces that you've built and how do you work with them to put their local fingerprint on that as well?

Braden Cooks 08:37

Yeah, absolutely. Well, the exhibit is a big space that it creates. And it's interactive, and it's very visual, and it's very graphic. It's meant not only to convey a lot of historical information but also to tell a story and connect the dots for people. I think a lot of the way that history gets told is sort of like these are artifacts of the past. We really wanted to focus on how does this impact us today? Why is this relevant right now as the starting point for really the history? And it's interactive, so it invites everyone to add their own stories, to add their reflections, what's missing from the exhibit. As comprehensive as it is, there's still a lot that could be in it or things that they might want to challenge and allow that to be part of the conversation. Because everyone is coming to this learning and with things offer to teach. We take that in from the outset of the exhibit.

So, one thing that we do is, as you alluded to, is we localize every exhibit where it goes in different cities around the country. When we do that, we're always invited. So, someone invites us to come, they just reach out and say, "Hey, can you bring this exhibit? We saw it or we heard about it." We form with them a community advisory group. That group can be neighbors who've lived the history, researchers, up to elected officials, organizers, people involved in these issues, key players, as well as just folks who have stories to tell. To say, what is the local history? What are the local stories that we really want to lift up and talk about that we think aren't being talked about or we think are just really important to continue talking about? We go through the history of that from, we can go all the way back to indigenous and First Nations history and all the way till today to kind of come up with--and I always say--example stories. Because telling the story, even of a neighborhood or a block is a life's work. So, this is really about highlighting examples of this history, examples of personal and human stories as well. Really, this is not only a process of localizing the exhibit, but also kind of passing the torch off to this group to take ownership of it, of their history, of the platform itself.

A lot of the time, we'll highlight existing and ongoing projects, both projects that are looking at history on a local basis and things that are undoing redlining organizations. So, try and use it as a platform to leverage the work that's already been going on and that will continue well after the exhibits there. The exhibit is an organizing tool, so it really is not just about education. It's really about getting people activated and organized around these issues and around the "so what now" of it. What we're going to do about it.

Ame Sanders 11:36

I really love that aspect of it, that you're invited to bring this to a community. Then, you localize it with their advisors and their local community members to help make it their own. Maybe you could share some of the examples of things that communities have done after this has been in their community.

-How Communities Use Undesign the Redline

Braden Cooks 11:58

Yeah, as I was just saying, as an organizing tool, there have been so many different outcomes of having this exhibit. I mean, it's been around...we started in 2015. We've really seen on-the-ground projects. We worked on a cooperative urban farm and Community Land Trust project in Trenton, New Jersey, that's really about land tenure and community wealth building. We've seen fair housing legislation passed in New Orleans. The city council came through the exhibits. Dollars have been shifted over to community wealth-building models, programs that are from nonprofits, and things like that.

The City of Columbus, Ohio, is in the process of--I think they're still in the process of--changing their zoning code and really revamping that. They use the exhibit to have conversations about what that means and why they need to do that in eight different neighborhoods. We've worked with health institutions on social determinants of health.

We're very proud to say that the exhibit was present in Evanston, Illinois, when Robin Rue Simmons, who's a person there, championed the first successful municipal reparations policy in the United States. She was able to use the exhibit as a tool in having that campaign in conversation. They're doing down payment assistance grants and other things for families that have been cut out of owning their own home for many generations, among other things. So, that kind of spans the gamut from a really smaller scale, but still, very impactful groups of people getting together to learn and to organize and to do things. Community development organizations that have been inspired to be formed, actually in Baltimore, to these bigger policy pieces.

One thing I'll just say--it has a life of its own in every place it goes. Because people come around it, because it's a tool that everyone can use, there's just so many different things that come out of any one exhibit. It's almost impossible to track it all and to know it all. I certainly don't. I mean, you would think I do it, but I don't know everything that's come out of it because there's just so much that goes on and so many different groups that use it, and that's really the dream. That's what we want it to do. It has been amazing to see.

-Community as a Verb

Ame Sanders 14:18

I guess I'd like to zoom out from that project because it's a beautiful project and a lovely initiative. It sounds so impactful. But I want to zoom out a little bit and talk about a little bit more conceptual things. Maybe talk a little bit about how you see the term "community" and what that means to you. Then the other thing I wanted to get you to respond to is, what is your vision for how a community, however you see that, can use design and collaborative processes like this to stimulate and move toward greater equity and social change. Beyond this one project, but just conceptually, how do you see those two things?

Braden Cooks 15:03

Yeah, well, you know, we've been working in the space of community engagement, community-based design. A lot of partners have of mine, and I'm sure many listeners are Community Development Corporations. All of these institutions and movements use the word community. If you're ever in that space, I'm sure some part of you grows a little weary of the term because it can be used in so many different ways and by so many different actors and not always, certainly, in the really robust, alive way that we would use it. I think that that's something that we've developed over time to think a lot about. When we say community, what are we really talking about? We pull from in our work when you talk about social design, certainly human centered design thinking, some social sciences, a lot of popular education methodology, which is really bringing people into a process of both learning and acting.

I think one of the frustrations I have with community engagement is that it ends up being limited in its imagination, and there isn't really a flow of information back and forth to really shape a project. A lot of time, it's what color the benches should be and that kind of thing. That feels more like checking a box for a lot of projects than it does something that is actually valuable to the project and thought of as something that is going to drive the project and allow it to succeed. We've seen that really across the board. We've seen community-based organizations that sort of have varying degrees of engagement really with the broader community. A lot of the time we hear that word, and it sort of refers to a certain scale.

One thing that I'm trying to promote is for people to think about community more as a verb than a noun. So, how are you doing community? Community is a set of relationships, a type of relating to one another. Doing community is something that an organization or that person or a neighborhood can do or not do and be doing more of or less of versus kind of community as a label. When you start to think about how we are doing community? Where's community coming into the process as a way of relating to one another? I think it starts to be much more concrete, actually, in terms of what we’re talking about.

So, when we look at a project like we were working with this cooperative urban farm, which originally was going to be just a nonprofit and run by a few people. It's now kind of become a sort of platform in some ways. That's all to the credit of the folks who are there to leverage that for projects of the neighbors. Someone has a food project, and someone wants to do gardening, and sort of the interconnections and exchanges that are happening in those spaces that are that are different than if they were just kind of a one-off.

One of the things that we look at a lot is actually the quality of ownership in a project. Who actually literally owns the project? Where's the wealth and the dollars coming from and going to? A nice example of that I can give is a classic example of community development of building of a grocery store in a "food desert." Some people say food apartheid scenario. But a neighborhood that is lacking in grocery stores and fresh foods and that kind of thing. An example that we've often used in Harlem on 125th is there were decades plus of organizing by people in the neighborhood, community organizations saying we need to a grocery store here. This is back in the 90s. It's a very different Harlem than from what we see today. They brought in a Pathmark grocery store, which is a corporate grocery chain. Millions of public dollars went into this project, and it was a success because, hey, we got the grocery store, right? That's what folks were advocating for. That was sort of where the imagination was. We just need a grocery store like other neighborhoods. But you know what, this is a corporate grocery chain. It was not known for having great pricing and great products. They have a handful of minimum wage jobs that they chalk up to job creation.

Fast forward to today, Harlem is a very different place, and that is gone, and what's going there is luxury development. So, you know, all these public dollars went into it. All this community organizing went into it, and what was really the public benefit of that in the long term? It seems to me that that model really ended up benefiting the private corporate shareholders of Pathmark a little bit more, maybe even than the neighborhood. So, when we look at a project, that's a classic economic development project. There are many like that happening even as we speak. But you look at a model that is really community-driven, and there are models that are cooperatively owned.

There are models that are doing community shares and shareholdership. There are other models as well. But, that's a model that is really starting with people in the neighborhood coming together as shareholders and cooperative members. Bringing in designers, oftentimes pro bono, and people like us who are trying to help out, going door-to-door, building up support, bringing them into the design process. These are oftentimes places where there's a lot more value added to the community. They're creating community kitchens. They're creating food programs. They're working with students. They're connecting to local farms, right? So, now they're looking at how do we buy from local and regional farms and bring in produce that way. So, there's a ripple effect out into this bigger, broader ecosystem. And they're the owners of it, so they want it to succeed, and they want it to last and they want it to continue on.

There's a lot of research that shows co-ops have longer life expectancies as institutions and businesses than not. And so, wow, you look at a process like that and you can say, that has a lot more public benefit. We can measure the wealth and the dollars that are being spent; they're going back out into the neighborhood, et cetera, et cetera. We can show how much more impact a project like that really has than the traditional economic development model. But there's very little in the way of the process and policy to get us to that model. Certainly, when you compare it to the old school, which is a private-public partnership to bring a grocery store.

What about a community-public partnership, where the public dollars and the millions of dollars that often go into those types of deals could go and flow actually back out into the neighborhood's pockets, right? I think that a lot of people are really engaged in those types of projects. There are many, many, many of them around the country. But we really don't have the infrastructure in our neighborhoods to drive those projects. One of the things is there's a lot of burnout. As I said, bringing in pro bono designers, doing door-to-door, they're often volunteers.

So, the real on-the-ground infrastructure that we need not only to do one of those projects, but do the next one on the next one and the next one isn't really being sustained or supported. So, that's what we think about when we think about social design, human-centered design. What is the role of the designer in terms of an activator of these types of projects and seeing the broader ecosystem so these things are not islands but actually feeding into one another? It's economic development. It's community development and social human development. It's really oriented around healing and repairing and forward-looking in a very optimistic way. A lot of the crises that we see today, from redlining, from environmental degradation, from wealth destruction, you name it. To my mind, we kind of know what to do, but the resources and the processes and infrastructure aren't really there yet.

-Building Public-Community Infrastructure

Ame Sanders 23:22

You talked about this idea of going from public-private partnerships to public-community partnerships. That's an interesting mind shift for us to be thinking about, and the examples you gave were really helpful. I just wonder what you think would be required for us to begin to have this kind of infrastructure in place in a community? Obviously, you've thought a lot about it.

Braden Cooks 23:48

Yeah, that was one of the impetuses for our concept around WELabs, which is something that we tested out and we work with in a few different places. And there are a lot of people. We work, for example, with a group in Baltimore at Impact Hub that brings together a lot of small organizations, incubating them and working with them. They are both nonprofit, for-profit, small businesses. You see examples like that around the country where those types of infrastructures are there. I think that there are two pieces. One is really that on the ground. People like us, people in community development corporations that are doing this community land trust. You see these types of projects that can really play a role of coordinating, connecting.

Then, I do think that has to be nested in some way in public policy. I think that it would be wonderful to really work through that. I'm not sure how many people have, but to really integrate into economic development, corporations integrate into ways that cities and towns and counties and states are directing resources to actual infrastructure projects, etc, into these types of ecosystems and projects and really supporting them and supporting the front end of design and development of them. Because, for example, after Hurricane Sandy, and back in 2008, we had a big recovery bill. One of the big focuses there was we're gonna fund shovel-ready projects. Guess which projects, which places have the resources to get a project to being shovel ready, which takes a ton of money, a ton of time to, all kinds of environmental impact reviews, you name it, to get a project to the point where it's, it's ready to break ground. These are often places with more resources, more infrastructure, etc. The places where there really aren't resources to do big studies and there aren't resources to bring up a project get cut out.

So, there's not enough investment in the front end of designing and developing these types of projects. And I think the opportunities there to say we're going to do it in a different way that's really community driven. It's not behind a desk somewhere in some government building that's where these decisions are getting made. An example of this is participatory budgeting, which allows folks to develop projects, come together as a community, vote on them, and see public dollars flow to those projects, which I think is a really amazing model.

The only caveat that I would give to that is a lot of the participatory budgeting that that I've seen, and I've been a part of it, ends up needing to fit into an existing box that a municipality or city has. So, it has to go to an existing agency, and it has to flow through those channels. Inevitably, many of the participatory budgeting projects I've seen are filling existing gaps in the funding world. So, they're fixing park benches or school light fixtures and like. Or they're doing things that the city already should be doing. I would say that that's not the right use of participatory budgeting because, really, those are things that the public already should be funding, but participatory budgeting really has an opportunity to allow for civic innovation. So, really engaging people to say what's needed? What do we don't have that we need? What are the pieces of infrastructure? How do we develop? I've seen some really fascinating projects come out of that. Projects are engaging with workers and street vendors and projects that create new types of parkland. I mean, you name it. That really think about the public realm in a different way and allow for people and citizens and residents to start to imagine and engage in the places where they live in a forward-looking way.

One of the things that I really feel has just become such a negative space and contentious space is in community engagement and projects, where I think for many, many people, really the only sense of agency that people have or feel they have is in opposing projects. That's where the agency comes from. It's like we can try and stop a project. But the idea of a creative agency, meaning to create a new thing, really isn't there. Our cities and our towns and places really need a lot of help, actually. Right now, there's just this blockade in some ways where the systems aren't really working together. They're not really aligned in a way where everyone's interests are aligned and getting transformative work done.

Ame Sanders 29:07

I guess it shouldn't be surprising coming from a designer, but one is this idea that our communities have insufficient imagination, or creativity to imagine into the future. This idea that they're less aligned and more able to oppose things or to deal with the things that are right in front of us that should already be being taken care of, rather than using the creativity of people in the community to imagine something very different and something much better. I have to let that sit in my head for a while to think about because it is a powerful observation about the state of our communities and the engagement of our neighbors and citizens in that community process. And then using community as a verb--that's an interesting twist as well.

Braden Cooks 29:57

Yeah. I think that's mainly because those are the opportunities that people have. I think if there were different opportunities to engage, you would see different energies emerge. So, I do think that that that's critical to understand. But the other piece I'd say is to go back to what I said about popular education. I'm really excited about multi-stakeholder cooperatives and how AI can drive things and all these different new, innovative ideas. But only because I learned about them. So, before I knew about them, I wasn't excited about them because I didn't know they existed. So, part of the idea of popular education is actually the sharing of ideas. It's not just to really be an objective social scientist who says, "What would you like to see in your neighborhood?" And people trying to imagine the things that they already know. Versus saying, how can we create spaces where people come together and learn about what other people are doing? What are other cities doing? What are the other models? What's something that's new that we're going to come up with? Engaging that in, as you say, a creative way and a forward-looking way. But I will add, critically, in a way that is really anchored in understanding the history of how we got here because that piece can't be lost. That is the foundation from which you can go forward in a way that will succeed.

-Advice to Communities

Ame Sanders 31:19

For communities who are listening and maybe they are, as I am, taking this in. And they are thinking how can I reorient the things I'm doing within my community to be more forward-looking? More creative? To have my community be a verb? What are some things that you would say to a community as advice for how they should begin to transition to this way of thinking and engaging?

Braden Cooks 31:51

Well, I do think it's a learning process. I don't necessarily say that I have all the answers and I'm here to comment. But I think that one thing that I would love to develop and love to connect is the community of thought, the school of thought, and all the people that are a part of it. Teachers and learners, who are the people listening, can gather people around and say let's learn about this, and let's share ideas ourselves. I think there is a piece of starting there. That's a big piece of why we have the exhibit is to say let's start with understanding how we got here and that until we do that, we're really operating in the dark. So, that's a big piece of my theory of change. You also can take stock of what you have.

I think that one thing that that oftentimes gets lost or that kind of gets fumbled, and when you start talking about creativity and forward-looking and all of this, is that actually, you really need to be about 75%, maybe more of you're doing what you already have. You've got what you already have and you're not trying to throw the baby out with the bathwater because so much has been done. So much is there already. Oftentimes, it's just waiting there to be connected to a process like this and to be activated in some way. That includes schools and students who can get involved and that includes community-based organizations. There are so many different groups that we've worked with that wish that they had the capacity to, in a sustainable way, be doing community to this point about the verb, really engaging and really connecting. But it's oftentimes an extra. When the budgets shrink, that's, like, the first thing to cut. There isn't this capacity for interconnection. I do think that we need that to be its own infrastructure and really to be supported. Supported by foundations and supported by spaces that are working in this. Inevitably, I think, by the public.

As I was saying earlier, as part of public infrastructure. Sometimes, a metaphor that I use is, we have a lot of bricks but no mortar. Mortar is something different. It's not the same as a brick. It's not another traditional organization. It looks different and works differently. We have to be thinking about that as a connective infrastructure. For example, we've worked in many neighborhoods where any number of different community engagement studies, research projects, all the city agencies are doing engagement processes around this or that, planning to go all the way down to a single site that does a process around what happens with this building. Where does all that information go? It really goes nowhere. It really kind of just lives in all these different places if it lives at all. A lot of the time, that disappears. What about just having that information in one place for any given neighborhood? People can keep doing and keep trimming out and just add to the pile, at the very least. But actually, a lot of it's redundant. Then, to say, there's something living about it. There's something iterative about it.

If I'm coming to do a new project, or there's a new process, I'm the city coming in, I can go and look at all the work that's already been done. I can go and look at what the community has already identified is what their needs are and map that out and understand that. In a lot of cities and places where you see those going on, and then they're sort of redone every few years and by different organizations and different people, and there's never really a connective piece where it's like, Okay, how are we sharing all this information? How do we see this information as a collective asset that we're all contributing to, and all, and it's not, that's not an organization is not another organization. That's actually a platform and a connective tissue. But there is to be implied in that maybe not an organization, but I agree with your point about a platform, but also perhaps some type of role for someone who's a community historian or librarian, or inventor of these things, because they don't necessarily live abstractly in a database somewhere. They have to be placed in the context of unity. And curated.

I mean, I would love to see local libraries take on that role, for example. That's a perfect institution for it. Libraries are such an underfunded institution. They are more popular than ever. More people are visiting libraries now than they've ever been. People think that that would be the opposite, but it's not. That's because they're a really important community and public infrastructure for people. A lot of people need them to use the Internet, for example. But you could imagine libraries that are producing knowledge about the community, about people there from data and housing data to community stories and oral histories. A lot of folks are doing that--seeing the library as a space where this type of engagement and knowledge and infrastructure can take place, as a platform in many ways for these different, not just the library, but community-based organizations and all kinds of folks. Libraries are very taxed, and really pulled to their limits as it is, so this is about really bringing in resources and space and redesigning libraries and supporting the people that are already doing this work. But that's a great example. Again, that would be a public community partnership, right? That would be something that is a piece of public infrastructure and then leveraging what's happening in the community.

-Housing and Wealth Building

Ame Sanders 37:56

As we think about Undesigned the Redline, a lot of cities and communities are working today on housing. How do you see the work that is going on in communities around housing tying into that into some of the other ideas that you have around design?

Braden Cooks 38:11

Well, you know, housing is at the center of the redlining story. So, it's obviously something that we've thought a lot about, and housing is something that has been tremendously uneven. For a long time, when you look at the history of redlining, at the same time that we redlined certain neighborhoods and said, "Hey, these are places where we're not going to invest." This starts with home loans, right? Although it bled out into bank branch locations and insurance rates and all these things. But this is really a lot of it was driven by the FHA (Federal Housing Administration).

But on the other hand, they're opening up this huge spigot of wealth building for homeownership. This is when we're inventing the 30-year mortgage or really opening up the idea of owning your own home as a core piece of the middle-class identity. This is going to explode the suburbs and really create this geography that's very uneven in the United States, where you have much wealthier, much whiter suburbs. Much disinvested, and a lot of people of color in cities. That's obviously changing now because of gentrification and things like that. But that basic geography gets invented through redlining, and this whole mortgage system. For a long time, homeownership was really a pathway to the middle class. It was an upwardly mobile pathway because of the way that we financialized housing in many ways through this mortgage system, but also just the production of a massive amount of housing. We've kind of stopped doing that. We have not been building enough housing. It's an absolutely massive issue right now--the need for new housing.

One of the reasons for that is that many green-lined areas, I would call it, "green-lined" areas that the FHA and others said are great places for loans; their value is based on exclusion. I mean, a lot of these places first had exclusionary covenants that said this is a white's-only neighborhood. By the 1968 Fair Housing Act, which is formally when we made that all illegal, by the time that's enforced by the 70s and 80s, you see this huge movement towards zoning. You get the single-family home zoning, different types of restrictions on lot size, on the size of your home, etc. All of these things end up basically de facto preserving the homogeneity in many ways of wealthier, whiter neighborhoods.

So, in a lot of desirable places, we're just not building housing. Now there's a movement, for example, to get rid of single-family home zoning, and a lot of places where they're putting what's called the missing middle. So, just a more gentle density--you know, row homes or smaller apartment buildings and things like that, or ADUs (accessory dwelling units, extra housing, maybe above a garage or whatever). People are really pushing back, saying, "Oh my gosh. We don't want these people." The language isn't that different from what it was, in many ways, 50-60 years ago or less. It wasn't that long ago. Still, we see a lot of really racially-tinged language around who gets to live in my neighborhood.

I'll just point out to everyone here that there are a tremendous number of studies that show that doing this does not decrease people's property values. Actually, people's property values tend to go up. So, that's a totally bunk idea, but it comes from this idea of infiltration, which is what the Federal Housing Administration uses. They called it hazardous infiltration. That's how they referred to people. Black folks, Hispanic families, and Asian families as hazardous. That idea is still pervasive in real estate. So, it has created a tremendous amount of problems in terms of the amount of housing stock.

Then the other issue to this is not because we're not building enough housing but also because of this financialization that happened with mortgages and things like that. Since the 1940-1950s, the median home value in the United States has gone up about six times inflation. Anyone who's trying to buy a home right now can tell you just how expensive homeownership has become. Because of how expensive it has become--six times inflation. So, it's six times as much to buy a home now as it was accounting for inflation back when my grandparents were buying a home. Because of that, instead of being a mechanism for upward mobility and middle-class wealth building, it has really become a barrier to upward mobility. A lot of people can't get into homeownership anymore, especially in markets where there are a lot of jobs and people need to work and find homes. And because of that, housing affordability is just really at the center of so many of the social crises that we're dealing with right now. How difficult people's lives are becoming. You got to keep in mind that the cost of a mortgage is very expensive, over a 30-year mortgage. Even back when interest rates were low mortgage is double (and now it's triple or more) the cost of your home. So, over 30 years, you're paying double or triple the cost of your home on a mortgage. We call this a great wealth-building scheme, but you have to double or triple the value to break even.

People build equity in their homes, and that's really important. I'm a big believer in that. I think then, inevitably, it's better than renting, for the most part, because you get to build equity. And it's for savings for most people. But it's basically because we're piling so much money into housing that, by default, it's just people's biggest asset. But I would question actually if we really should be looking at it as our number one source of middle-class wealth is your home. Especially considering that, for most homeowners who live in their home, it's not a rental property. If they want to sell it and they want to get access to that money, they have to find another house. And that house is also going up in value. So, the idea that you're going to make all this money off your home is a bit of a misnomer, especially in a lot of places and especially for a lot of people who've been cut out of intergenerational passing down of wealth that's happened through real estate. It's really just not working anymore.

So, we've been looking at a lot of community ownership models, affordable ownership models. The example that I gave is the reparations approach with down payment assistance grants for people who've been cut out of homeownership. Building wealth with them, getting homeownership. There's a ton of different models to look at, and really focusing the housing system on getting access and affordable access for more people, especially as we're going to be building a lot more housing, I'm hoping because we just desperately need it. The push is there to build a lot more housing over the next 10 years or more, that will really be thinking about that. That this isn't going to be exclusive again because we have the opportunity not to repeat the cycle of exclusion when it comes to this new housing that we're going to build.

Ame Sanders 45:28

I love the idea that your project, Undesign the Redline, and other types of community participative activities and design work can be used to address this and to imagine within a community a different way for the housing needs to be met. And for people to have safe and affordable housing and build wealth through that as well, but at least have safe and affordable housing, which so many people don't have today.

Braden Cooks 45:59

Yeah, and I think it's really innovating on the wealth-building piece as well. So, the way that I frame this project is to think about, we've talked about the American home as your nest egg. Well, what we need is a nest plus egg, or a nest and an egg model, which is to say, we're gonna focus on the nest and homes and affordability and making sure everyone has access to that and beautiful places as well. I just want to say that. I come from design. I think a lot about that. I think really being intentional and beautiful and human-centered in the design of those spaces is critical. It's something that's often not talked about very much. It's thought of as sort of a secondary issue in this space of affordable homes, but I don't think so.

Then the other piece of that--so that's the nest and an egg--which is like, really, how do we look at community wealth building and folks getting access to building wealth? What is the next model in America for the American nest egg? What is the future of the American nest egg? We need a broad-based wealth-building policy. We need to rethink that. I think it's over half of baby boomers are going to retire with no savings. It doesn't get any better than that as you go down the generations. People have things like 401ks and that type of thing. Some people do, those are even being questioned now as to how effective that's going to be. Really, we have the opportunity to look at things like community investment funds that are partnering with local governments that are embedded in communities, that are funding local businesses and local economies, doing economic development, infrastructure, investing in new housing, investing in new energy projects, etc. By bringing in community ownership, community shareholders, and community owners of those where we as a neighbor, I can start to build up my retirement fund and have it be invested in my neighborhood, in my region, in a sustainable economy and new energy projects invested in my infrastructure.

Right now, for example, we know that the municipal bond market is really shrinking, especially in smaller towns. People have really trouble raising money, and it's becoming much more expensive. So, how do we get folks involved in that? So, I think that there could be a lot of opportunities to really look at centering doing community, as I said before, in terms of wealth. One of the things that's a contradiction in housing is a lot of people say, "Well, I just want to see my property value go up and up and up." While that's good for the homeowner because, presumably, you're going to build wealth. Of course, if you want to buy a house next door, when you sell or even somewhere else, you're still dealing with that same problem. But it's creating a crisis of affordability. What about aligning that where building the new housing down the street? I'm actually one of the investors in that because I have some shares in the community wealth fund. I can see that those new dollars coming into my community are benefiting me, too. So, I am really trying to think about how you go from these systems that are not aligning with people's interests.

People see their interests as opposed. They don't want to see these things happen to say, actually, my interests are aligned. When new investment comes in, when it benefits more people, I actually see my own benefit grow. We haven't really had the tools to do that before in these really robust ways. We look at the platforms and systems and kind of from the technology just to do it, the smart contracts, things like that. Things that really streamline all of that process, just to the on the ground infrastructure that I was talking about, in terms of community engagement and getting these projects off the ground and getting something to become investment ready. We've worked with a lot of social impact investors and people who are looking for community-based projects and projects that are doing social good. They say, "Well, there just aren't enough investment-ready projects." Particularly in places like redlined neighborhoods, where, guess what, there just aren't the resources to get it to that point where it's investment-ready, right? There aren't people with Master's in Business and lawyers and things like that and all these people that are going to create these projects together so that they're ready. So, we do need that front-end piece. And I think that that's really what's missing, even from this housing question.

Something that I'm particularly interested in, and more conversations I want to have with more elected officials and people employed in political leadership really about shaping policy around this. You can look at local, state, and federal policy. Another hat that I wear is on the board of the New York State Sustainable Business Alliance. We represent about 3,000 in a network of businesses that are socially oriented, oriented around equity oriented around community in many ways, that have very different interests than a lot of the Chamber of Commerce type people, folks that you hear from.

So, we're often making a business case, for example, for more sustainable practices, or more equitable practices with workers, and showing how that's really good for business and small business especially. Regional, local businesses, if you change the material, for example, in packaging to more sustainable packaging products, you find that instead of being manufactured around the world, through all these chemical processes, we actually have a lot of local farms, for example ,in New York that are doing hemp that are doing all these things. This money can flow back into a regional economy. So, you know, you see that the connection between doing things in a more sustainable way, a more equitable way and a more in a way that's actually driving those resources and dollars more locally.

But as I was saying, with the policy piece, somewhat as part of that Sustainable Business Alliance, we were looking at the Build Back Better legislation, some of which ended up getting passed in the Inflation Reduction Act. But in BBB, there were a lot of proposals for regional hubs, technology hubs for innovation, for investment, really in main street that I think could be leveraged. That type of policy could be leveraged for a lot of what I'm talking about. I think it would be great to start curating, bringing people together to talk about how we can look at bringing together this really great top-down policy with bottom-up processes and bottom-up infrastructure and how that sort of top-down can support the bottom-up in a much more robust way. I think it's all there in many ways. But I do think that, as a country, we need to be thinking about that. The way that I was thinking about it is just to say, what is the next American nest egg? What is the future of Main Street?

Main Street has really a vision for community that people can--it's very accessible, right? We all know what a main street is. There are different types of main streets. There are redlined main streets in many places that were disinvested and used to have a lot of small Black-owned businesses, for example, and now don't. There are small-town main streets that are also disinvested that really need support and local economies that used to drive dollars and circulate dollars through a community that isn't anymore. There's even, I would say, suburban main streets, which don't kind of exist because they were never really built. We don't have a need to do infill development and build really wonderful beautiful village main streets that are where diverse people can come together and thrive.

So, all of those spaces, all those Main Streets, need sort of a new plan. That was some policy pieces, that framing that we were looking at, to really bring this full circle and say how do we really envision this as a society in a way that brings people together? Because I really do think we're in a crisis of community right now, where relationships and community relationships have been deteriorating for some time. People are more and more isolated than they've ever been. They find themselves more and more antagonistic and opposed to these bigger systems and government systems and things like that. They don't see them as working for them. There's very little positive interaction where they can see these types of systems and processes supporting them and helping them in a democratic way. What I love about things like a Community Investment Fund, or these types of projects or public community projects, or whatever it is, is democratized. It is really engaging people, letting them determine what's going to happen and become the driving force of what's going to happen.

-Conclusion and Recap

Ame Sanders 54:57

So, I love how this discussion brings us back to probably a pretty good place for us to close out here, which is that we have been and are facing somewhat of a crisis of community of interaction with one another and using community as a verb together. What you've given us today in our discussion are so many creative ideas about how both policy and design and robust engagement and relationships with the people that we interact with, live around and depend on, how that can help us change and build a future that is more equitable and more inclusive, and how we can exit this crisis of community if we focus on those things. So Braden, thank you so much for this discussion.

Braden Cooks 55:48

Yeah, thank you. It's been a wonderful discussion. I'm happy to be here and connect with the community that you connect with. It's wonderful to be able to speak to them.

Ame Sanders 56:01

I knew this conversation with Braden was going to be rich, but I had no idea the breadth of the territory we would cover. I'll try to recap a few points that stuck out for me. We know that in many cases, our communities were founded on and physically built around racist policies that, by design, kept our community separated by race and class and reinforced the concentration of wealth. These were conscious design choices. They're not accidents of evolution. Braden reminded us that we still live with and are surrounded by the legacy and artifacts of those designs and community choices. This conversation with Braden reminded me of a William Faulkner quote, "The past is never dead. It's not even past."

Still, my conversation with Braden wasn't just stuck in the past. As designers always do, Braden helped us imagine a future, a new design, if you will. Braden reminded us that we can't just move on as if the past did not happen. We have to understand our community’s history and how we got to where we are today. We have to consciously undesign before we can redesign. Then, we have to consider entirely new ways and practices of designing our community's collective future. So, Braden didn't just talk about new ways of designing the future; he gave us examples that illustrated just how we could do this. So, Braden talked about focusing on social and human-centered design for community projects and initiatives. Shifting investments from public-private partnerships to public-community partnerships. Establishing innovation hubs and funding design resources to support the front-end development of projects in underserved communities to enable them to tap into more resources and grants as they become available. Leveraging practices like participatory budgeting in our government funding. Braden also talked about reimagining uses for and expanding civic infrastructure like libraries to become platforms for enabling community engagement, information asset management, and building hyperlocal community knowledge centers.

He even talked about imagining a new way of thinking about our nest egg. You know, he had the idea of separating our nest from our egg and finding new avenues for local wealth creation. He talked about better engaging community members earlier in the process, and around aligned interests to enable us to move beyond the opposition we so often see today.

But perhaps the most powerful point that Braden made, at least for me, was that we should think of the word community not just as a noun but as a verb. We should actively be doing community together with our neighbors, and it's through actively doing community together that we are then able to undesign the systems and built environment that structure our communities today and design and build a more equitable, inclusive future to better serve us all.

This has been the State of Inclusion podcast. If you enjoyed this episode, the best compliment for our work is your willingness to share the podcast or discuss these ideas with others.

If you'd like to hear more about the practice of building an inclusive and equitable community, head over to theinclusivecommunity.com and sign up for our newsletter. And, feel free to leave us a review or reach out. We'd love to hear from you.

Thanks so much for listening, and join us again next time.

CONTRIBUTORS

Guest: Braden Cooks, Co-Founder of Designing the We

Host: Ame Sanders

Social Media and Marketing Coordinator: Kayla Nelson

Podcast Coordinator: Emma Winiski

Sound: FAROUT Media