Episode 55, 51 min listen

In this episode, we learn about using the power of community truth-telling as a springboard for systemic change and equity in Cincinnati, Ohio. We talk with Kim Rodgers from the Center for Community Resilience (CCR) at George Washington University and learn how they provide on-the-ground support to communities, like Cincinnati, to advance progress toward resilience and equity.

AUDIO PLAYER

Listen on Apple Podcasts or Listen on Spotify

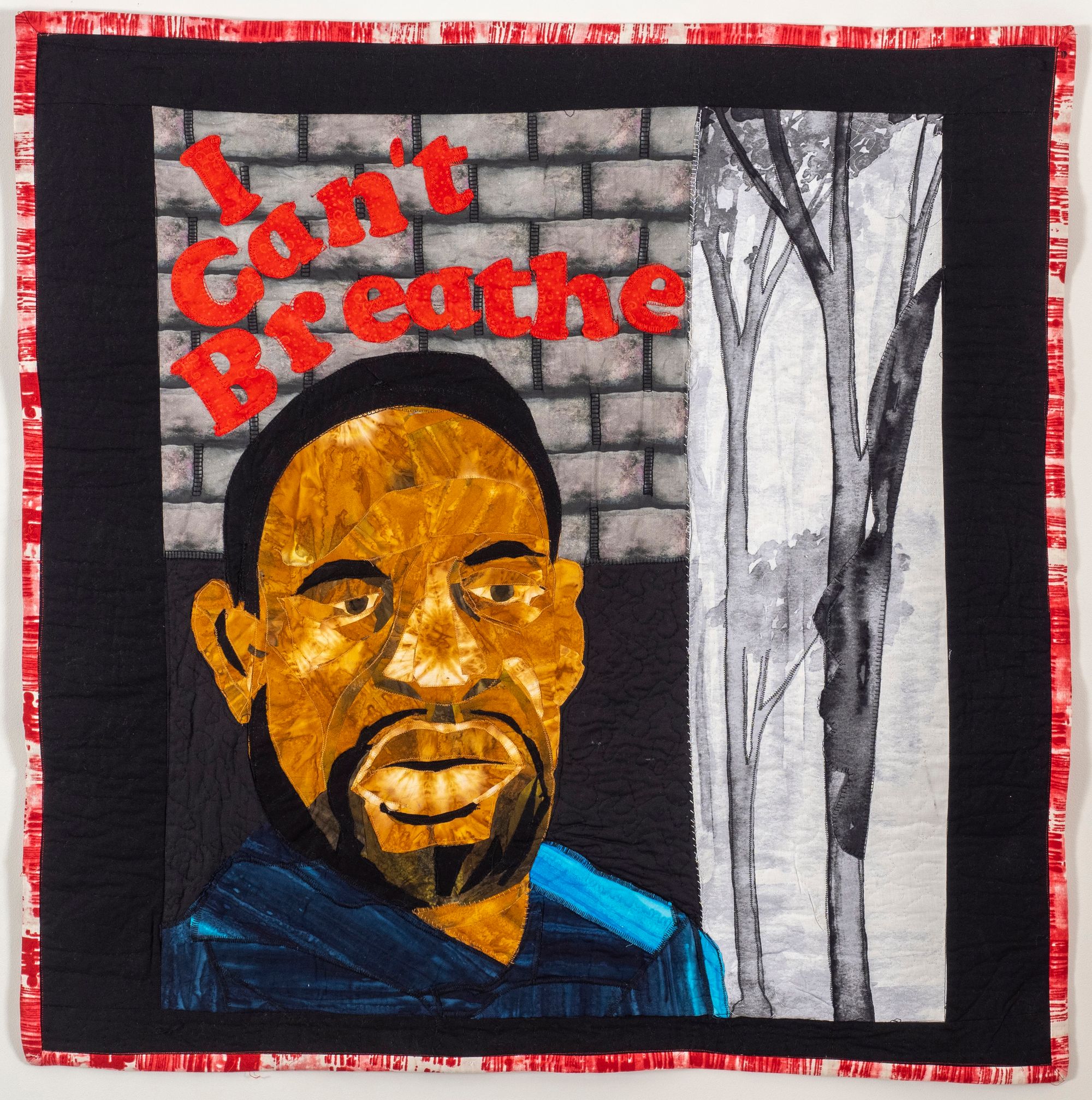

Kim shared some images from CCR's work in Cincinnati and nationally.

Clockwise they are: 1) One of the quilts Kim mentioned, Breath- An Ode to George Floyd. A Quilt by Peggie Hartwell of Summerville, SC, 2) Group Model Building session, 3) Filming the Cincinnati documentary, 4) Hill Day with Cincinnati Partners, 5) 2023 Center for Community Resilience National Convening

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

Learn more about the Center for Community Resilience at George Washington University.

Watch America's Truth: Cincinnati documentary.

Part of our discussion was about the great museum partnerships in Cincinnati. You may have been surprised, as I was, to learn they are home to the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. It is definitely on my list of places to visit.

If this episode interests you, you might check out these episodes as well:

Episode 53: Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation. I interviewed Jerry Hawkins about his work leading the nonprofit Dallas Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation. He also shares that his city's work is part of a larger TRHT movement happening in communities and universities all across the country.

Episode 11: Racial Truth and Reconciliation Through Community Remembrance. I interviewed our local leaders of the Community Remembrance Project of Greenville County, S.C., and their work to commemorate the victims of lynching in Greenville County. We also learned about the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, AL, their work with communities across the country, and their Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Episode 54: Making a Commitment to Equity with Conserving Carolina. I interviewed Rose Lane, and, at about 13:29 in the audio, she shared her thoughts about the power of narrative.

KIM'S BIO

Kim Rodgers leads the Fostering Equity portfolio and Building Community Resilience Collaborative in the Center for Community Resilience (CC) at George Washington University. In this role, she provides technical assistance to CCR’s national network of partners, helping them articulate and dismantle structural racism as a root cause of racial, social, and economic inequity. By facilitating narrative change and community power-building opportunities, Kim is working to catalyze the co-creation of structural and systemic solutions that foster equity and improve community outcomes through collaborative, cross-sector action.

FULL TRANSCRIPT

-Introduction

Ame Sanders 00:11

This is the State of Inclusion Podcast, where we explore topics at the intersection of equity, inclusion, and community. In each episode, we meet people who are changing their communities for the better, and we discover actions that each of us can take to improve our own communities. I'm Ame Sanders. Welcome.

In Episode 53 with Jerry Hawkins from Dallas Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation, we heard about the importance of community truth-telling on a community's journey towards equity. And, in Episode 54, with Rose Lane from Conserving Carolina, we talked about the importance of stories and narratives as the gatekeepers of the facts we let in, and how stories and narratives can be so important in preparing the community soil for equity and inclusion to take root. If you enjoyed those discussions, you're gonna love this episode.

This episode continues those thoughts and carries them a step further, as we learn about the power of truth-telling and narrative change and how it is leading to systemic change and equity in Cincinnati, Ohio. If you're also interested in understanding more about how leading universities support communities to help them advance their local work of resilience and equity, then this episode is for you. Today, we are happy to welcome Kim Rogers. Kim leads the Fostering Equity Portfolio and Building Community Resilience Collaborative in the Center for Community Resilience at George Washington University. Welcome, Kim.

Kim Rogers 01:51

Thanks for having me, Ame.

-About the Center for Community Resilience (CCR)

Ame Sanders 01:53

I'm really interested in learning about the Center for Community Resilience. What's the focus of the center and the work that you guys do?

Kim Rogers 02:01

Sure. So, the focus of the center is really to work with communities across the country who are trying to address the root causes of childhood and community adversity and trauma.

-Defining Resilience

Ame Sanders 02:03

How do you define resilience?

Kim Rogers 02:10

So I think for us, resilience is really about a community having the ecological and environmental supports across systems and sectors to really be able to bounce back. Not just bounce back, but really thrive in the face of difficult conditions or difficult issues or challenges that are happening.

-Equity and Inclusion at CCR

Ame Sanders 02:35

How do you see equity and inclusion playing into the work that you guys do at the center?

Kim Rogers 02:39

Equity is at the center of everything that we do, and so when we think about trauma, or we think about inequity, something is missing, right? Whether that be resources or opportunities or investments. So for us, creating community environments where there's equity means that we're able to make folks whole where they haven't been previously. The inclusion piece is interesting because we don't tend to focus on inclusion. There's a reality that inclusion can exist, and equity still might not exist. So, you can have people at the table, but if they're not being really woven in, listened to, elevate their voices and perspectives, etc., then equity will never happen. So, inclusion is a part of this, but equity is really the main goal for us.

-How CCR Works in Communities

Ame Sanders 03:29

One of the reasons I really wanted to talk with you guys and with you, in particular, is that you and your team, sort of step out of the university setting and take this work into the community. So, can you tell me a little bit about the work you do in the communities that you partner with?

Kim Rogers 03:48

Pretty much across all of our programs, everything that we do has a community-centered focus. Whether we're doing a project that we have come up with—so, for example, our Resilience Catalysts in Public Health Initiatives works with local health departments across the country to help them engage communities and engage partners across sectors to try to address whatever challenges they're seeing that are affecting community health. In that case, yes, this process that we've developed to guide them through we came up with, but when we go into communities, we're not telling them, here's what we want you to work on. We go in, and we ask folks, "Okay, what are you experiencing? Where are the biggest challenges? How do you think we should address them?"

So, everything that we do in community is really centered on following the community's lead in terms of how the projects go. For example, with this Resilience Catalyst work, yes, the process for all of the health departments is the same, but no two health departments are going through that process the same way because the community context is unique, and we have to treat it that way.

Ame Sanders 04:51

So, you're working with health departments all across the country, but you're also working with a network of communities as well, right?

Kim Rogers 04:58

Yes. So, our Building Community Resilience network is actually the first network that the Center for Community Resilience had. There are five sites. They're in Dallas, Washington, DC, in the Baltimore area, so the DMV area, we call it--DC, Maryland, Virginia. We have sites in St. Louis area, Cincinnati, and in Washington State.

So, with them, that work was really formed from a community-centered aspect, as all of our work is. But they've been together for about seven years and have gone through this really long process of really learning how to center community in everything they do because when we started working with them, they weren't all sure about what that process was like. So, when that collaborative started, it was actually focused on healthcare institutions. There was a realization very quickly that to be able to address childhood adversity and community adversity, you need people from across the community and folks from different disciplines in different sectors involved. So, those regional networks have each sort of grown and expanded to now include K-12, education, academia, and direct social service organizations. So, that's just a little bit of background context. Since they've all now gone through the process, we're looking for opportunities to pilot initiatives with them, because they have such strong cross-sector coalitions in place and such deep community connections from doing work with CCR and amongst themselves for the last seven or eight years.

So, one of the projects that has been an output of that is our Truth and Equity Initiative. That initiative exists to dismantle structural racism through three focus areas: narrative change, power building, and systems change, which is really about us using policy and advocacy to try to advance a community-driven agenda that targets issues that the community has outlined are creating harm and creating adversity.

-The Role of Narrative Truth-Telling in Dismantling Racism

Ame Sanders 07:01

There's a lot of stuff I want to ask you about. That sounds so interesting. So, one thing that I know you and I share a common interest in, and maybe it's a place to start, is with narrative. So, you mentioned that the Truth and Equity Initiative dismantles racism and narrative as part of that. Maybe you can talk a little bit about how you see that. How do you see narrative contributing to that, and how do you use narrative to make a difference or maybe even to shift narratives that have been maybe not the best narrative in the past?

Kim Rogers 07:32

Yeah, absolutely. So, you know, let's be real. When we look right now at the landscape of our country, there's a lot of effort to push back on the truth of how we got to where we are today. When we think about the ways that structural racism is maintained. Dr. Wendy Ellis, our director, came up with this graphic where it sort of outlines how structural racism is upheld. There are three key pillars, and that's narrative, policies, and practice.

So, when we think about narrative, narrative is really what drives the ability for folks to justify (or obscure if they'd like to) inequities. So, map that back again to this movement that we have to limit our youth education and exposure to the very difficult and challenging and not pretty actions that this country's government and power holders have made throughout time to get America to where it is. We start to see how these things--and when I say these things, I mean, narrative, policy, and practice get woven together.

So, for us, as we do the Truth and Equity work, truth has to be the starting point, right? Because the reality is, when you go into a community, there are going to be different levels of knowledge and awareness about the root causes of the community's context. So, in one neighborhood, things can be beautiful. They have all the resources they want. All the access. Lots of green space. Good schools. You go two miles down the road, and you could have a completely different environment where there are no grocery stores. The quality of the school, and the education is not as good. There are not as many programs for youth to go to. The streets aren't safe to walk. The built environment is challenging for people. And I think there's folks who would look at those two different communities and say, well, something's going on with the people in Community B where the where the conditions aren't that great and whoever's in Community A where things are wonderful, they must be doing the right things.

But the reality is truth-telling a narrative change allows us to shift people's understanding of inequity from this very individually-focused lens where you're asking what's wrong with people to a more systemic view that really looks at, okay, what has happened to people? What decisions have intentionally been made over time that have created these inequitable conditions? So, once we get people on the same page about that, it really allows us to move forward with a collective and shared understanding about the historical and personal realities of what is happening in a place and then use that to drive the way that the community is able to make decisions that help to change those conditions.

Ame Sanders 10:19

Wow. So it sounds like that is so foundational or fundamental to the work that you do.

Kim Rogers 10:21

It absolutely is.

-CCR's Work in Cincinnati, Ohio

Ame Sanders 10:23

One of the things that you and I spoke about earlier, before the podcast, was that you had done some work in Cincinnati. I was wondering if you would maybe talk a little bit about that, because I know, I'm not sure of all the work that you did, but I know that they have done a lot of work on telling their history honestly and reflecting that back to the community in a more honest and truthful way.

Kim Rogers 10:50

So, Cincinnati is where we piloted our Truth and Equity Initiative. That was started, in the wake of, that spring of 2020, where Breonna Taylor, where Ahmaud Arbery was killed, where George Floyd was killed. We had this national uprising with people, particularly in this time, where because it was the early days of COVID, everybody was at home and glued to their TVs. So, all of these really, really traumatic things happened in the public sphere, and folks were having to really grapple with the reality that we don't live in a post-racial society, that structural racism is alive and well here in lots of ways, and there's something that needs to be done.

So, for us at CCR, again, Cincinnati is one of our original Building Community Resilience sites. Having had a relationship with them for seven years, and also understanding the context--Wendy often refers to it as a blue dot in a red state--there was a lot of appetite from the folks in that coalition to really address structural racism head-on in an area where that's not necessarily something that people are comfortable with or people are doing. So, there is this very sort of perfect storm of conditions where everybody's eyes were on structural racism, we had a site who was really committed--and not just the site again. They are a coalition. It's not just one organization in Cincinnati. There were multiple organizations. But we had a coalition of folks in the Cincinnati region who were ready to take action.

So, Wendy being part of the Aspen Ascend Fellowship program, and one of her colleagues, Laura Huerta Migus, who at the time was the executive director of the Association of Children's Museums, thought, "Okay. What if we partner to do some kind of truth-telling and reconciliation work?" So, that's where Truth and Equity was born. The whole idea was to facilitate this local coalition in Cincinnati through this process of creating shared understanding about the history of structural racism there, working together and expanding and connecting with other folks in the community to gather a collective understanding of, "Okay. Here's the history, but also how is it affecting people?" So, a two-pronged thing. How do we engage the community to help share these stories and spread this? Also, how do we gather community input to establish and craft a community-driven policy agenda, where then the folks on the ground, with the support of CCR, could start working towards that policy and advocacy to address the priority issues that came up through the community engagement process?

It's funny, because I think it took us some time of working with folks in the coalition. So, we would have monthly meetings and in those meetings, the first six months was a lot of level-setting. So, we did an "Understanding Narrative" presentation. The partners that we had at the table were the University of Cincinnati's Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation Center, who was at the time led by Dr. Tia Sheree Gaynor, who has now moved on to the University of Minnesota. But the University of Cincinnati's Truth Racial Healing and Transformation Center, an organization called Learning Through Art Inc, the Cincinnati Museum Center, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, a local organization called Elements, which uses art, culture, and hip hop to really engage youth in the community. We also had Cincinnati Public Schools at the table, and an organization called All In Cincinnati, which is really focused on engaging the community for systems change. Oh, and I can't forget we had one of our original BCR partners, who was called Joining Forces for Children and that in itself is a coalition of other organizations.

So, we built this really beautiful cross-section of organizations who are coming in from different angles with different priorities, but who all recognize the importance of tackling structural racism as something that affects the clients and the mission that they're working on. So, we guided them through this process of like learning and level setting for the first six months. Then we divided up into subcommittees recognizing that this was a project on top of their daily work. So, that subcommittee format really allowed folks to focus on an issue that really played to their strengths or that they were really interested in. There were three subcommittees. We had advocacy and education, community leadership development, and arts and storytelling.

So, for again, maybe the next six months, those subcommittees were working together to sort of figure out, "Okay. We know that we need to engage community. We know that we're trying to get to this policy agenda. How can we do activities that help weave those things together?" So, some of the things that that folks did.

The advocacy and education committee was relatively straightforward in that we had an understanding of the challenges that were happening. Housing was a big one. Living wages for Black women. Black women's maternal mortality. So, there were sort of these issues that were already on everybody's radar and level of awareness when we came in. So, the advocacy and education committee was really thinking about, "Okay, what are some opportunities for us to address those issues.?" So, for example, one of the things that they ended up doing, because, of course, things are always emerging, right? So, as we're doing this project, we're also getting all of these anti-CRT bills that are coming up, including in Ohio. Of course, with Cincinnati Public Schools at the table and with the university at the table and recognizing that those bills are going to affect their business and the way they operated, it was really important for us to mobilize around that quickly. So, within that subcommittee, they helped to organize a letter and some testimony that was shared. Eventually, that bill, I believe, actually, it never got passed. I think it might still be on the table. But part of the advocacy that that group did helped to at least make sure in that moment that wasn't getting passed. The art and storytelling committee, so just an example of the kind of work that they did.

Having the museums as part of that was a really beautiful thing. Also, having Learning Through Art, which really works with young children to incorporate art into learning and healing. We worked with them to develop an exhibit that was installed at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. So, this exhibit was curated by this Black woman named Dr. Carolyn Mazloomi, who leads the Women of Color Quilters Network. Again, after George Floyd was murdered, she put out this call across the world asking people to send in quilts just to give them a way to express how they were feeling about the reality of not just that situation, but the ways that structural racism has existed for centuries in this country. And just the most beautiful quilts got sent in. So, luckily our partners that Learning Through Art, Kathy Wade, had been working with Dr. Mazloomi already on curating this exhibit. We were able to weave it into this Truth and Equity Initiative. So, this exhibit goes up in the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. It's on display the entire summer. People are able to come in and really engage with this beautiful, but also very tragic in lots of ways, expression of how structural racism hits people and how it hurts people and the sort of things that you have to grapple with in looking at that head-on. So, that was a really cool way to invite the community to reflect in that way.

But to really create even more expansive engagement, Kathy's team at Learning Through Art, with the support of CCR, launched this community engagement project called Story Quilts. So, it really inspired by this idea of like these quilters had done these beautiful things, what if we make our own story and patch together our own community's feelings about structural racism? They were in person, and they were virtual, but everybody who came would get a blank quilt square and crafting materials. There were facilitators who would guide conversation, and through that conversation, people would be doing their quilt square. So, it was a way for people to be able to engage with an issue that's difficult, but also express themselves and do it if they weren't comfortable expressing themselves verbally. Because there's a lot that goes on. There's a lot of discomfort that comes with having to talk about and acknowledge structural racism. The art in the quilt squares gave people a different place to express that. So, it was a really wonderful experience. These community conversations were hosted across the Greater Cincinnati region, and the organizations that hosted them eventually pieced together the quotes from each one, and they're hanging in their specific organizations. So, that was a really beautiful thing that happened.

Then the Community Leadership Development Group, which I was the lead of, we actually launched an Equity Champions Leadership Development Program. So, what we did was put out a call. We had applications, but this was a very short turnaround process as well. As long as the applications were, you know, people were interested, we accepted them. We actually only ended up getting 10. So, it was a perfect number. That's what we were looking for. But these were community members and folks who are in leadership positions, but maybe not even in the traditional sense. Like they are either emerging or, if not a leader in their own organization, a community leader. People who are connected in communities and want to be able to do some kind of initiative that helps to address structural racism. So again, similar to what we were doing with the broader Cincinnati Truth and Equity Coalition, we worked with this Equity Champions group, and guided them through a very similar process of like level setting, creating shared understanding. We involved some healing aspects into their work. All of that eventually led to--also, of course, there was there was lots of dialogue. Dialogue is such a critical piece of this work as well. Putting yourself in the position to be able to learn from other people's perspectives, share your own perspective, and find somewhere in the middle was a really important piece of this.

At the end of the initiative, everybody presented these action plans for how they could try to affect some kind of change in their sphere of influence. So, some folks had plans to do racial healing circles. I don't know if you're familiar with the racial healing circle concept I think was developed by Dr. Gail Christopher, who used to work at Kellogg and now leads the National Collaborative for Health Equity. Racial healing circles are really a way for people to come together and find...the purpose is not commonality, if that makes sense, but to come together and be able to see other people for who they are without making assumptions. So, some people were focusing on doing racial healing circles with people who had been previously incarcerated.

We had a guy who was going to do a collage experience. So, similar to Story Quilts, he was going to facilitate conversations with people about identity and power, and all of those things and build collages with them. We had a woman who was coming from a predominantly white community where people weren't really trying to talk about these issues. Her idea was to develop a conversation series where she would actually bring in different people who are working in the space or who have ideas to share and then facilitate conversations between her community and these other folks.

So, a lot of really cool stuff came out of that. And it offered us a model for how we could build and support and empower folks who are already working in community and already trying to make these changes to create more equitable environments with feeling more confident, more capable, and connecting them with other people who are trying to do the same thing. Because depending on where you are, it can be a really lonely process to try to push for something that it feels like nobody else wants. Whereas really just, even if other people want it, the socio-political context might make it difficult or feel like it's going to be a real challenge. So, to be able to have a sounding board and a network of folks to work with on that, I think, was really powerful.

So, when you think about the scope of the kind of project, as you can see, there were lots of elements and lots of moving parts. It was really important for us to work on addressing structural racism in Cincinnati from these various sorts of angles.

As we were doing all that, simultaneously, we were doing a documentary. The funny thing is, when we started that, you know, we thought, "Oh, we're just going to do a quick 10-minute something to sort of highlight an issue." And as we started filming and as we got in it, we realized, "Whoa, there's a lot of threads here that really need to be brought to the surface and woven together." So, we ended up doing a full-length documentary called America's Truth: Cincinnati, where we looked at in depth the ways that structural racism in various forms harmed these four Black communities in the region. It was just a really powerful way to capture the scope and magnitude of the issue and do it with a combination of historical evidence around policy around practice around funding decisions, but also through the lens of the people who lived through it and have experienced the consequences of it. Really, that's where the beauty of this is.

Again, when you think about the fact that you're trying to transform the conditions in a community, you can't do that without understanding that community's experience. So, it was so important for us to make sure that we were elevating the voices and the existing work because people there were already doing work on these issues. It wasn't CCR coming in, or the coalition coming in and sparking all of this. There's already a lot of amazing organizing and activism going on there, and we just wanted to bring that to the forefront for people to see. It really worked. We surprised ourselves to see, you know, how powerful. Every time we showed it, people were a little bit mind-blown because it really shows, again, how big of an issue this is and the various and the different ways that structural racism operates on a structural level.

I think that was the other thing about this. We weren't talking about burning crosses or that more interpersonal thing. We're talking about things that are codified into the very systems that we have to operate in every day. Because of that, because it's been codified for so long, are often hidden if you don't dig. So, digging all of that up was really important. A really wonderful thing actually happened in June of this year. We had been working with councilmember Scotty Johnson in Cincinnati and also Vice Mayor Jan-Michele Kearney and sharing this information with them. Through that education of the council, with the documentary being a huge piece of uncovering some past harms that were actually supported by that very local legislative body, the Cincinnati Mayor and the City Council issued a public apology and a proclamation to one of the communities in the documentary. So, the West End, also known as Kenyan Barr, for the approval and facilitation of one of the largest urban renewal projects in the country that displaced nearly 27,000 people who were 97%, Black, with this promise that they were going to house them in better conditions and then they just weren't able to do it. Not for lack of trying, but because of that socio-political context.

At the time, it would have required integration, and the white folks in the community were just like, "No, we're not doing it." So, people who had had had been in this place that was that was really thriving--in its own way, right? Not wealthy, necessarily, but culturally thriving, strong social cohesion. They lost a lot and had to disperse. Wendy and I went down to Cincinnati for the proclamation. There were people there whose parents had lost homes, who had lost their businesses, and they had an opportunity to speak, and it was just really heartbreaking to hear the ways that the social fabric of that community was dismantled by this sort of facade of progress. When the reality is you have to always be asking in these, in these instances, progress for whom?

So, the documentary has really become a really great example for us about how we can weave in that truth piece--how we can help change the way we talk about narrative change. How we can change the way people who are thinking about communities who they see today, the community is struggling and may have no concept of why. Being able to show--I really hope to shift people's thinking. So again, that narrative change, and that's where we started and in a big old circle. But narrative change really is the starting point for getting people to think about new ways of responding to inequity that don't just cover it up or put a band aid over it, but really transform the structural factors that are underlying the inequity.

-Unpacking Lessons from Cincinnati

Ame Sanders 29:27

So, there is so much to unpack and that story that you just shared. So, I want to take a minute and do that with you because I think there's so many points that I'm just so interested in and want to bring out. So, first, you talked about these three different groups. The group that was focused on advocacy and education. The group that was focused on arts and storytelling. Then the one that was focused on community leadership. So, those are areas that, in our work and State of Inclusion, we call preparing the ground. So, it's preparing the community ground to be able to make the changes and to be willing and prepared to make the changes that are necessary that are more structural, more systemic.

So, I love that you covered all of those, and they're part of your work because I think that they're all such relevant elements to that.

The other thing that I take away from that, and I've heard this from other people that I've talked with too and other communities, is this is really, while you guys were expert facilitators and resources and it seems like there were a lot of outside resources, expertise and methods and things that were brought to bear. This work is still at its heart an inside job. It is unique to the community. It grows out of the assets and strengths and talents that exist in the community, like your story about the quilts is fabulous. That's not something that another community can just replicate because they don't have that, that person, that culture, that whatever. But the ideas that come out of that can be repurposed and reconsidered and reused in different contexts. The fact that all of the things you described are so unique to Cincinnati. Their history was unique. The groups that were available. The assets that they had. The people who were committed to this and came around the table with you to work on that. It's something we've heard over and over again and I think it just bears repeating. Because it's not like someone's gonna come parachute into your community and save it for you. You have to be willing to do that work yourself.

The other thing that your story reminds me of is how long the timeline was for this. So what you told us, what I took away from this, is that, first, you had a group who had already been working together in some sort of intact kind of way for seven years. Then they, because of those relationships, (and we know relationships are everything) they were then able to move into this new, and perhaps more complicated and challenging, arena. They had some catalysts that happened around them and some tragedies that occurred with the murders of George Floyd and others that sort of sparked some interest.

So, I think of this timeline, thinking about the timeline, and also the importance of over time building relationships is so key to what you described into the success of it. Then the other thing that I thought was interesting, too, is--so sometimes I interview people, and they work for an organization. In that organization, they have a mission or objectives, and they see themselves moving that forward. But what you described was a broad coalition, almost like an ecosystem of people who were working on equity and inclusion. You also, in your leadership role, you actually trained up more people for that. So, I think this idea of an ecosystem of people in a community working on equity and inclusion is something that's been in my mind lately, and is intriguing to me to see that that was part of your work in Cincinnati. Whether you call it a coalition or an ecosystem, or how you think of it. Do you have any ways that we should be thinking of it based on your experience?

Kim Rogers 33:33

Well, I think what you're sort of alluding to is the reality that what we try to do in our work is, as you said, facilitate. We have expertise in the areas we have expertise in. But the reality is the community knows the community best and has the best sense of what direction to go, what's going to work and what's not going to work, how we should be going about things, and who we should be connecting with. If us as an organization, and particularly at a well-respected academic institution like George Washington University, if we don't bring ourselves into community and build that trust and build those relationships and let people know, "Yeah, we know what we're talking about. But you guys do too." There's not a lot beyond whatever time we're there for that can happen.

So, I think part of this too is, again, in whatever ways we can, helping to share our expertise. Share the power that we have. Instill that into the community to strengthen what's already there, because every community already has a great--No matter what is happening there, there are assets. There are strengths. We have to always remember that. I think that can be a challenge for people who are at the organizational level trying to do this work. I think we're just socialized to understand whose knowledge, whose expertise has value, and who has mattered, and that usually is folks who have letters behind their name or who are affiliated with a specific organization. But when you let go of those preconceived notions or assumptions about who has something to offer, it really changes your ability to authentically work with folks and community.

There's this sort of dual learning that has to happen. We're learning as much from the community as they are from us. That actually strengthens the ability to do the work. So, as we as we do these kinds of projects, everything that we're doing is with this intention that when we leave the work will continue without us. We don't want people to have to rely on us, although we're very happy to make ourselves available if you need support, yes. But we don't want to be the sort of gatekeeper of progress, if that makes sense.

So, in everything that we do, we're really trying to leave people with the tools, the resources, and knowledge, the relationships, to be able to facilitate their own progress at their own pace, and in whatever ways feel aligned with them and what their missions are. Whether that be in some sort of specific coalition-centered project, or just in the day-to-day work that they do on their own or even in their own personal lives.

Ame Sanders 36:30

I think that's so helpful as we think about this. I'm really glad you shared all of that because not setting up or bringing in or structuring, in some way, gatekeepers to this progress is so fundamental because we really want a million seeds of progress on this to be able to grow and bloom in the community, as the community is able to make that happen. There are a couple of other things that I wanted to unpack from what you had said earlier, too. This example that you have shared with us is so rich. I know it is to you guys, but it is to me listening to it.

So, first, is that you were also sure to meet people where they were. I loved your story about the racial healing circles. We've heard about those before in some of my interviews, but I think that's really important that we just sit with the truth of one another and our lives and our experiences, and we find a way for people to do that. But then also the idea that some people are not comfortable expressing themselves verbally about some of these challenges. It's very difficult. The story of making quilt squares as part of a work so that people have other paths for expression besides just verbal, which can carry a lot of weight and can create some anxiety for people that are afraid they're going to say the wrong thing or do the wrong thing. So, I think that was really insightful for you guys to take that approach. Then I think to share that with us, it's really important for us to reflect on that too.

Then, the other piece that I loved about this is that out of all of this, there came these artifacts of the work that you did, which became impactful themselves as individual things. The documentary, the quilt displays--those in themselves bring goodness into the community and help that conversation, but they become artifacts that the community can then rely on over and over again, as they move forward.

So, oh, my goodness, Kim, that was such a great example. Thank you for sharing all of that, because I think I'll have to listen to it a dozen times before I can get all my takeaways, but those were just some of the ones that I picked up from what you were saying. I think our listeners will find a lot of value in that as well. So, one of the things that it makes me want to ask since we're almost out of time--I could talk to you about this for a long time, but it's just we're almost out of time.

-Advice for Communities

So, let's say that communities are listening to this. What kind of advice would you give them for a community that's on this journey? Because as you described being with Cincinnati, they're already on a journey. They're already doing work. There are people already advocating for things. What advice might you give a community who wanted to promote charge, if you will, their work across the community?

Kim Rogers 39:30

Yeah. I mean, I think one of the biggest things is to start somewhere. Which is to say you don't have to have some beautifully crafted or articulated or fully fleshed out plan to begin the journey towards community transformation, whatever that means to you. I think a lot of folks feel hesitant, particularly if resources are light or they're working in a place where the issue that they want to address most other people may not think the same way. I think the most powerful thing that folks can do is just to believe that what they're trying to accomplish is possible and just take one step.

I forgot who said it, but there's a good quote that I like to think about when it comes to this long-term work. I think that even in my early 30s, I may not see the fruits of this labor just because the fact that I work on structural racism. It's so deeply entrenched. You talked about laying a foundation, and we're tilling the ground.

There are so many ways to till the ground. It could be a one-on-one conversation with a family member. It could be a small photo project, where you just use your iPhone to take some pictures about what's going on in the community and talk about it. There are lots of ways that don't have to be hugely transformative on their own, to start the process. So, really my advice is to think about, how you can affect change right within whatever sphere of influence you have. So again, whether that's your friends' circle, the book club you're at, or the PTA organization that you're in. There are so many.

We all have relationships with people, and there's a way to leverage those relationships to try to make those small changes. If you're able to accomplish that within your sphere of influence, well, guess what? Everybody in your sphere of influence also has a sphere of influence. So, there's this sort of slow osmosis or expansion of whatever gospel, so to speak, that you're trying to preach. Eventually, over time, as you continue to make the small efforts and small steps, you look up 20 years from now, you've gone a long distance that you didn't realize because you were going inch by inch. So, that really is my biggest advice. You know, big change happens with small efforts and small steps, and we can't overlook the power of those more minute or micro shifts in the big picture.

Ame Sanders 42:18

I love that notion. John Paul Lederach calls it critical yeast, the yeast that's in the community that sort of creates this change over time. So, I really like that idea. Thank you for that advice. Also, I want to revisit one of the points from your story about Cincinnati that I think is also worth bringing out, which is you talked about your group that was working on advocacy and the fact that they saw in the moment something happening that they needed to respond to right away. I think it's also this idea that we keep our eyes open to what is going on around us and that we don't become so focused on a plan or a specific outcome that we miss the opportunity to either benefit from something that can help catalyze the work or respond to something that perhaps can become a barrier that isn't yet. So, I think that was also some wisdom from your Cincinnati discussion that I took away as well.

-Moving from Narrative to Action

So, Kim, we've talked about this tilling the soil as you said or preparing the ground. But obviously, the community will want to move into more structural changes and begin to address some of the systemic issues that get uncovered or surface during this kind of process. So, maybe you can talk a little bit about some of the things that you've seen in that regard, either with Cincinnati or with other communities that you've worked with--how they transitioned into making the structural kinds of changes.

Kim Rogers 43:57

Sure. So, I think probably the best example is in Cincinnati. Once we had gone through sort of phase one of that process, which I talked about, we ended up with this policy agenda that had several priorities on there. One of those priorities was housing. It really opened up an opportunity for us to get creative about how can we tackle this issue in a way that, yes, supports Black communities because we know homeownership in Black communities is far less than that's also the main way that folks build wealth in America. So, when you think about the wealth gap, housing is the big piece of that.

So, we, in collaboration with some partners on the ground, launched a Closing the Racial Wealth Gap study to dig a little bit deeper into challenges with homeownership in Cincinnati. This work is ongoing. What really makes it unique is, when we talk about equity or inequity at CCR and even when we're talking about structural racism, there's a reality that I think some folks don't understand that sometimes the policies, the practices, the narratives that were maybe initially intended to create inequity for people of color, can have these aftershock effects for white folks who maybe have lower socioeconomic status. So, in Cincinnati, that is actually the case in some places.

So, what we did was in an effort to sort of build a more collected and more global approach to addressing housing that gets at what we wanted to get at, but also brings in this demographic that maybe folks would think, "Oh, well, why are you working with a predominantly white community on this?" They're being harmed as well. So, this Closing the Racial Wealth Gap study is working with a neighborhood called Avondale, which is predominantly Black, and a neighborhood called Riverside, which is predominantly white.

Through this initiative, what we're trying to do is dig into, from the community's perspective, the factors and the challenges that are creating barriers to homeownership and trying to find a way to weave and find the commonalities between those two so that we can (1) we will have research evidence around what needs to be tackled, but also (2) now we're building power in two very different communities who can then bring that power together to both advocate when the time comes for policy changes that could really be transformative.

Again, going back to this idea that what we're trying to do is not just us lead the way and pull people along. We're trying to create relationships. We're trying to create this competence, this awareness, the skill building, and the understanding so that the folks that are living in these communities can continue this work on their own. I'm excited to see, as this work expands and we eventually get to policy priorities, how these two communities, who again could not be more different, can come together to demand change on an issue that's affecting them both in ways that they may have not even realized.

Ame Sanders 47:18

That's a great example of how to move from sort of this narrative into action. It emphasizes again what you've already told us: that building relationships, finding ways to share power, establishing, and facilitating without directing, that those are important things in this next step as well as you begin to transition into more systemic or policy-related changes. So, Kim, thank you for sharing that, and thank you for sharing your time with us today. I really appreciate the discussion.

Kim Rogers 47:51

Thanks for having me.

-Conclusion and Summary

Ame Sanders 47:56

The information that Kim shared about their work with Cincinnati was jam-packed with nuggets of wisdom. While there are many efforts across our country to push back on truth-telling and to stand in the way of honestly facing structural racism and history, we heard how the city of Cincinnati is embracing the painful truth of their racial past. But they're using it as a springboard to build a more equitable and resilient city. We heard how Kim's team at the Center for Community Resilience served as a facilitator, a helper, and provided methods and tools. However, they clearly understood that the essential role of transformation and leadership happens within the community itself.

Kim reminded us that the community knows the community best and that communities do not want to bring in gatekeepers to progress, but rather find helpers and facilitators who can foster progress and support them to let many seeds for progress sprout and grow. You know, I loved hearing how Cincinnati had tapped into the unique assets and talents of their community. That included world-class quilters, their incredible museum partnerships, their long-standing coalitions, their leaders who stepped forward to be part of leading transformation, and their community members willing to share their stories and their family stories of harm and loss as part of their documentary.

Kim told us that we should let go of any preconceived ideas that we have of who has something to offer in this work. We all have something to offer. Kim also reminded us that they started with this foundational work, but when they started, they always had an eye to the future and the goal in mind of ultimately making policy and systemic change. Then she talked about how they had moved from examining their past to building their future.

As Kim talked about the futures work in the area of housing, she reminded us that while systemic racism can harm Black communities, there are often aftershocks that harm us all, and that by working together we can build more powerful relationships and coalitions for progress and change.

As we wrapped up, Kim reminded us, there are so many ways to till the community soil and that we just need to start somewhere. That by starting with even small actions, within our own network of relationships, and our own sphere of influence, we can create ripples and incremental change over time and that through consistent effort, we will find over time that we have progressed a long way on our journey toward equity.

This has been the State of Inclusion podcast. If you enjoyed this episode, the best compliment for our work is your willingness to share the podcast or discuss these ideas with others. If you'd like to hear more about the practice of building an inclusive and equitable community, head over to theinclusivecommunity.com and sign up for our newsletter. Also, feel free to leave us a review or reach out. We'd love to hear from you.

Thanks so much for listening and join us again next time.

CONTRIBUTORS

Guest: Kim Rodgers

Host: Ame Sanders

Social Media and Marketing Coordinator: Kayla Nelson

Podcast Coordinator: Emma Winiski

Sound: FAROUT Media